Chapter 2: Git Architecture

Thu, 25 Sep 2025 14:49:24 +0530

When you build any project, the first question you need to answer is what you need as requirements, or what you want to build to solve the problem that you have.

Suppose I want to rebuild Git from scratch. I will not go to the developer and say "build Git," and the developer will start coding it.

Of course not. You will first sit with the developer and start explaining what problem you want to solve, or what are the things you do manually that take your time and you want to automate, what are the important features that must be in the system, and what are the optional features that would be nice to have.

In our case, let us start explaining what we need Git to do.

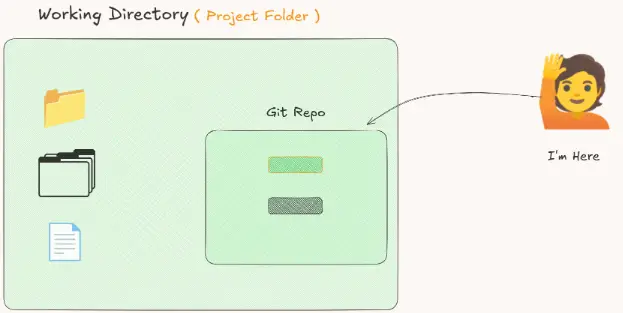

Suppose I am working on a project inside a folder or a directory just like this:

We will start using some Git terms. Instead of "folder" or "directory," we use the term working directory, which means the same thing. In Git, we often call it the working tree, which also refers to the folder that contains the project files.

After some time, I added some changes to my project. So it is not the same version as before. It will be, for example, version 1.1:

Nothing happened. We just modified and added some code to the project. We still see the same thing.

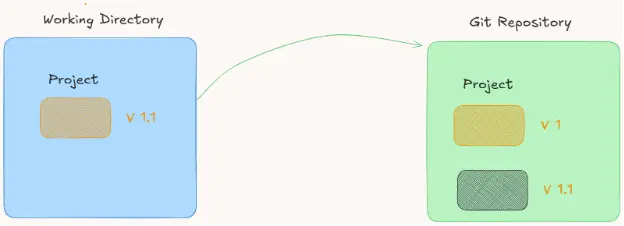

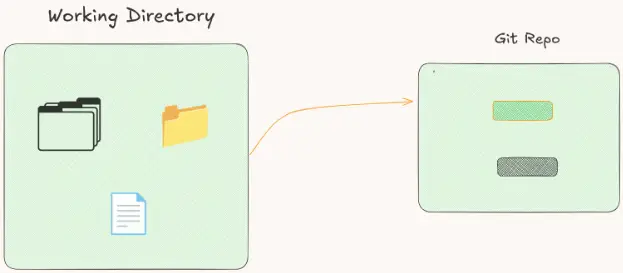

We do not see Git working now. But under the hood, Git will do this:

Under the hood, it will create another directory. We call it the Git repository, or in short, Git repo, in which it will save the state of the project. It will contain the version v of the project and version 1.1, who made the changes, when they made them, and what was changed. All of this will be saved in that repo.

But in our project folder, we only see the same files. Nothing changed, because all the work is saved and handled in the Git repo.

So now, as a requirement, you need Git to track the files. By "track," we mean track the changes, what is added or removed in all the files and folders inside our project. That includes file names and the code inside, everything.

We also need this to be portable and to work on any operating system. If I work on Linux and switch to Windows, for example, it should still work. So it needs to be system independent.

I also need everything Git tracks to have a unique ID. We said that Git tracks files and folders, so everything should have an ID.

I also need to track the history. By "history" we mean all the versions that we have, what changed from version to version, who made the changes, and if a developer makes changes and later undoes them and goes back to a previous version, I also need to know all of that.

The last thing is we need to track files without changing anything in them. Track the file as it is. Do not do any modification to it.

Now that we have these base requirements, the developer can take them and start working to build Git.

Now the question is how can we start applying and doing this tracking? The first thing we should do is change the format of tracking files.

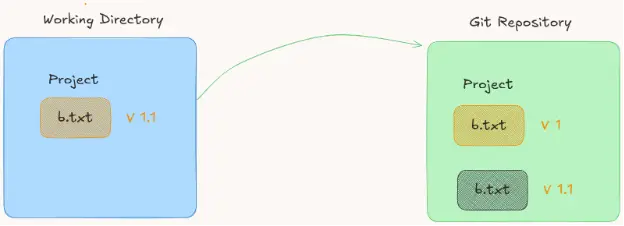

Let us take an example like this:

Now if we take this example where we track files by their names — OK — but what will happen if I delete the file b.txt and I make another file with the same name b.txt but with different content?

In this situation, is it a new file or is it the same file as before? What exactly happened? And do we also need to track the file names?

We cannot track files by their names only. The names themselves also need to be tracked. That is not logical, right?

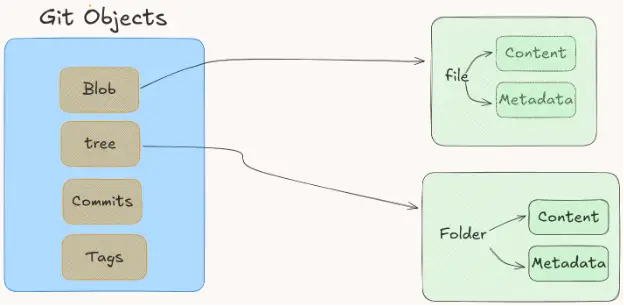

For this, files and folders should be transformed into objects inside the Git repo.

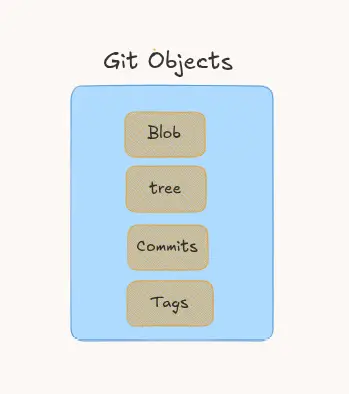

Objects in Git are not only files and folders. There are some other things too:

We said that objects track files and folders. So where are they?

Actually, the names are just changed, magic names, right? 🥸

blob

This fancy name actually means a file. If it means a file, why not just write "file" instead of this crazy name?

The answer is that we do not just track the content of the file. We also track the metadata.

Metadata means the type of the file, the size, the date, and so on. Metadata and content together give us a blob 🤗

tree

Basically, this means a folder 😡

Again, why not just use the simple and understandable name "folder" instead of "tree"? 🤔

Again, because it contains the metadata of the folder, such as size, types of files and folders inside it, and so on. All of this makes a tree.

The other types (commits and tags) will be explained later, and we will understand what they do also.

We call folders and files objects because they contain not only the folder and file data but also metadata about them, not just regular files and folders. I hope you understand the difference.

Now, we’ve solved the problem of tracking, right?

OS Independence

Let’s move on to the second requirement: OS independence.

How can we achieve this?

Git has something we call a folder structure. This structure contains all the information about the repository, and the best part is it works on any operating system. It's just a folder.

Most of the content in this folder is simple files. The encryption is straightforward, and all the files are compressed to make them faster to read.

You get the point: a Git repository is just a simple folder. It doesn’t contain any databases or complex systems, just plain files.

Portability

Another useful feature of this structure is its portability.

If you take this folder to a Windows system, for example, you’ll still see all the modifications that were made on Linux. This makes Git highly portable.

Now, you might be wondering:

“If I have a project on Linux and copy it to another environment like Windows, how does Git come along with the project?”

Great question!

Remember when we said that we have the working directory and the Git repository? What Git actually does is create a special folder for itself inside the project directory.

🤷 So, whenever you copy your project folder, you’re also copying the Git repository with it!

This hidden folder is called .git. The dot at the beginning means it’s hidden by default.

Typically, the folder that contains both your project files and the Git metadata is called a repository, or repo for short.

At this point, we’ve understood how Git achieves portability and OS independence.

unique ID

The third thing is the unique ID and track history. Now, we use blobs and trees. We do not use names as identifiers anymore, so we need another way to identify which blob belongs to which file, or which tree belongs to which folder, and so on.

For this, there are several ways to implement it. We can use, for example, a hash function that generates a hash for everything, a file, a folder, or even a single character. This hash function can generate a unique hash code for each, and it will be unique depending on the file. It should also be deterministic. This means if I pass the word "git" to this function, it should generate a unique hash. And if I pass the same word "git" again later, it should generate the same hash, not a different one. This is very important.

The question is: does this already exist, or should we build one from scratch for Git?

Yes, there are a bunch of hashing algorithms that do the same job, like SHA (Secure Hash Algorithm), which has different types such as SHA-1 and SHA-2. The difference lies in how many characters are generated for the hash. There is also MD5, and others.

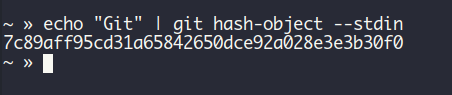

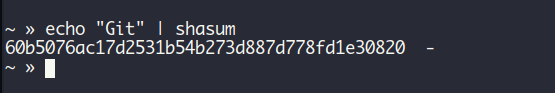

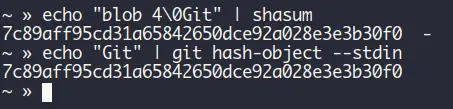

Git uses SHA-1 to generate unique IDs for objects, and you can see this with a real example in your terminal. If you try to get the hash ID for the word "git", it will look like this:

In this example, we print the word "Git" and pipe it (pass it) to git hash-object, which is responsible for generating unique IDs for objects in Git. It gives us a 40-character ID as a result.

–stdin tells Git "Don't read from a file, instead, read the data coming through standard input(echo)".

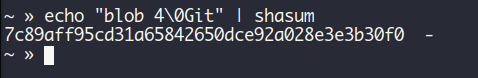

Now let’s go a bit deeper. We said that Git uses SHA-1, and there is also a tool in Linux called shasum that uses the same algorithm to hash files. Let’s try it with the same word "Git":

Hmm… wait. You said that git hash-object generates a deterministic hash and that shasum uses SHA-1 just like Git. So why is the output for the same word different? 🤔

Great question and observation. This is true, but the answer is that Git does not just take the content of the file. It also takes metadata and some other things into consideration. If you remember, we said that earlier. Yes, but this is just a single statement, not something inside a file, right?

Actually, it is inside a file. And Git takes this into account along with three other things:

- The type of the file

- The size of the file

- And a null character at the end

So if you give Git the word "Git", it will calculate all this and add it to the hash ID. It does not just take the word as it is. That is why the result is not the same.

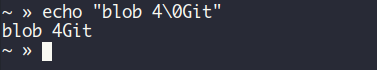

Now, with this in mind, if we take the same word "Git", Git sees it like this:

echo "blob 4\0Git"

blobis the type4is the size (you see only three characters, but there is an escape character for the new line at the end)- followed by the escape character

\0 - and then the word itself

All of this is combined together. hash-object generates an ID for it.

If you echo the word using echo, it will give us this result:

Now, if we take the same final string that Git sees and pass it to shasum like this:

It will give the same output as the one generated using git hash-object.

This is just a simple demonstration of how Git works and how it takes the metadata we already explained. We said that Git doesn't just track the content, it also tracks the metadata.

Up to this point, we explained how Git tracks everything, how it is OS-independent, and how it generates a unique ID. The next step is to understand how Git tracks history.

If you remember, we said that the unique ID (the generated hash) changes if we make any change to the file, whether it is the name or the content. Even if you just add a space to the file, the hash will change.

What Git does is take the newly generated hash, compare it to the saved one from the last change, and check if they are the same. If they are the same, it means you did not make any changes to the file. If they are different, it means the file changed. Simple, right?

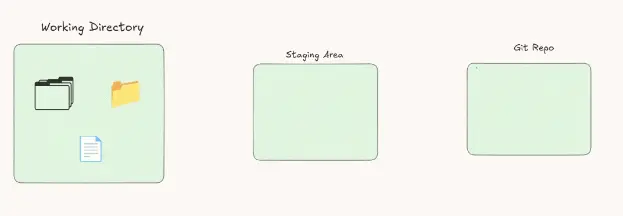

Let's continue our journey exploring the Git architecture. Old VCS systems (some of them still exist and work) used something we call a two-tree architecture. What does this mean? It is just like we already explained. We have two folders: one for the project and the other one for the Git repository.

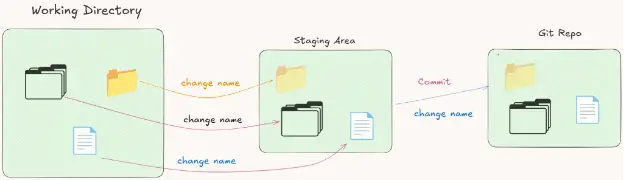

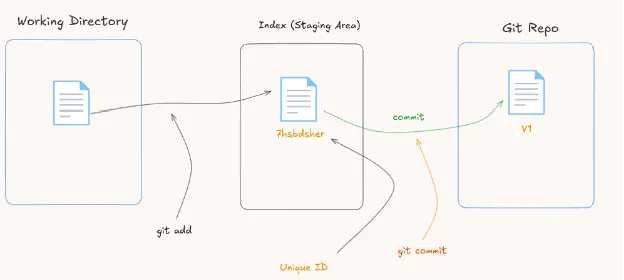

Wait, doesn't Git use the same architecture? No, actually Git uses a three-tree architecture, which means three folders (trees), like this:

In between the working directory and the Git repository, there is another tree called the staging area, or the index.

I will tell you something cool. This staging area is actually a file inside the Git repository. If it is just a file, why do we call it a tree?

It looks like a tree, but physically on the machine, it is just a file. And we are going to learn what it does in a moment.

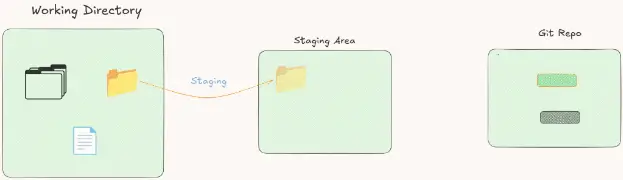

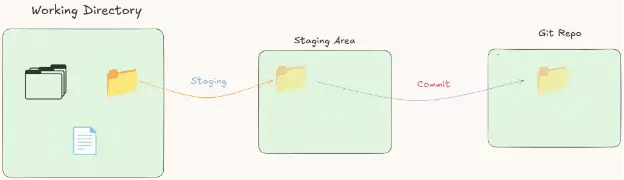

We place this tree between the repository and the working directory because it performs a task between the two. Suppose you are working on a file and you make changes to it. Instead of putting it directly in the Git repository, we put it in the staging area. In simple words, we prepare the file to send it to the Git repository.

So basically, the staging area is where we place the file to get it ready to be saved in the Git repository. We call this operation of sending the changes to the Git repository a commit.

A commit is the operation of saving objects in the Git repository.

Okay, so if that is the case, why do we need this staging area? Why not send the changes directly to the Git repository? It sounds useless, right?

Well, it is not just that. There are other features of this staging area. Otherwise, Linus Torvalds would not have added it.

Suppose you make some changes, then you revise them and decide to change something. Before sending it to the repository and having another version, you can make that change in the staging area, compare it to the last version, and then when you are confident, send it to the repository. This helps avoid having plenty of versions. You get only one good version.

Another useful thing the staging area provides is the ability to group multiple changes into one commit. Let’s take a concrete example. Suppose you are working on a web project and you receive an order to change the name of the website. The name appears in different places in the website. What you will do in this situation is change the name in every place, and when you complete the modification of all your files, you send them to the Git repository in one commit.

So here we have multiple changes in the staging area for the same thing, the name, but in the commit it is a single commit. One version in the Git repository instead of multiple versions.

You get the benefit now. Instead of sending the changes directly to the Git repository and getting a new version each time, we make all the changes we need in the staging area, then send them all at once.

This area is also useful in troubleshooting. You can compare versions and see the difference before the changes are in the Git repository.

Another thing you should know is that the working tree is not always just a folder on your machine where you can do whatever you want. Sometimes, it can be the server or an online project for the client. So it is not always an open area to play. You need a place to verify and think before making changes online.

If you do not like using the staging area in Git, you can combine both steps, staging and committing, into one command.

Okay, that is understandable. But in the beginning you said the word "index" for the staging area. What is that?

Yes, the staging area is also called the index. Let’s take an example to understand this point and another important one.

Let’s say you are just starting a project and you create one file like this:

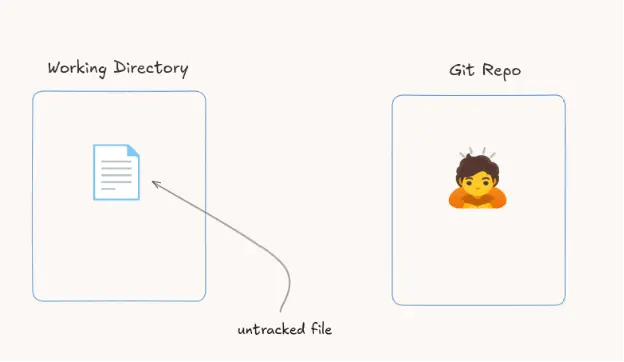

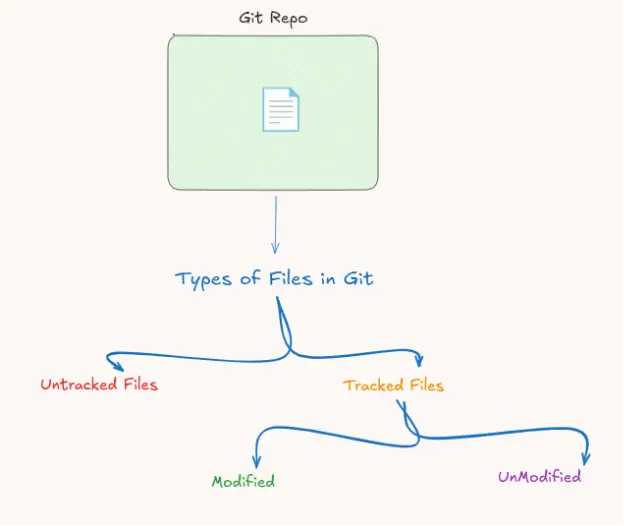

In this case, you have the Git repository, but it is empty. It does not contain anything at the moment. Now that you have a file in your project, Git cannot track it yet, so this file is untracked.

The first thing we need to do is make the file tracked so that Git can see and track it. Git is sad because it is not tracking the file.

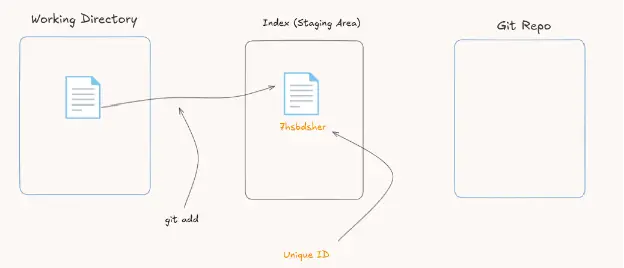

The area that turns the file from untracked to tracked is the staging area. What happens first is that the file gets hashed and assigned a unique ID.

The command that makes the file tracked in Git is git add. When the file is tracked, its unique ID is registered in the index, which is the staging area file. I told you that the staging area is just a file.

Simple, right? The file gets hashed in the staging area and all is set. What happens next?

Git creates a blob (a file) with the same SHA-1 created in the staging area. So now Git can track it and create version one of the file, right?

The answer is no, not yet. The version is created only after you do the next step, which is git commit. Now we have version one, and this is done using the command git commit.

So after the git commit, Git creates the first snapshot (let’s say a copy of the project) for the project. So now you get the idea: git add is sending the file to the staging area (staging files), and git commit creates the first snapshot of the project.

If you are just starting the project and you create a new file, the git add will change the file from untracked to tracked.

If the file you are working on already exists and has many versions already in the Git repo, it will be modified, and this brings us to another concept in Git called file state.

Git, inside the Git repo, classifies files into two categories: either the file is tracked or untracked.

The untracked files, as we explained, are the files that are added from the staging area to the repo. Git sees them but cannot track them until we make a commit.

The other type, tracked files, can be modified. This means the last commit of that file in the Git repo is not the same as the one you are working on in the working tree. You changed something, added, or removed anything, and Git categorizes that file as a modified file.

The other type of tracked file in Git is unmodified. This means the version in the Git repo is the same as in the working tree, with no modification.

These are the states of the files inside the Git repo. We use U as a short form of the word Untracked and M to refer to files that are tracked and modified.

You are going to see this in action when we start working on the command line and apply what we learn here.

This is basically the Git architecture in a short and simple way. I hope you understand how Git works.

What we explained here is the fundamental architecture. There are some extra things that we will learn later, but this is necessary to understand in order to get the full point of how Git works behind the scenes.

Recommended Comments